John le Carré’s son joins the Circus with his new book

- Harkaway, son of novelist John le Carré, has written a new George Smiley novel, Karla’s Choice.

- Though initially reluctant to enter his father’s literary world, Harkaway embraced the challenge as a creative risk and tribute.

- Despite his reputation for serious spy fiction, John le Carré was also a fun and playful guy — a side that deeply influenced Harkaway.

When David John Moore Cornwell (better known by his pen name John le Carré) passed away in 2020, he left his family a letter of wishes. In it, he requested that they ensure he becomes the most famous writer of his generation — and, if it’s not too much bother, the most famous writer in creation forevermore.

It would seem an imposing request from a talent who spent his life rising to equally imposing challenges. Le Carré’s parents were distant, and his father erratic. Nonetheless, he graduated from Oxford and went on to work for both MI5 and MI6, Britain’s security and secret intelligence services, respectively. As a novelist, he broke through the ramparts the old literati erected to keep the pulpy hordes of genre writers out, and as a public intellectual, he engaged in high-level policy debates on issues of global consequence.

He brought this experience and political knowledge into his espionage novels, which the critic Timothy Garton Ash once described as themed around “the endlessly deceptive maze of human relations.” Those themes and all-too human characters won him the recognition and respect of readers and fellow novelists, including Ian McEwan, Graham Greene, and Philip Roth.

Like I said, imposing. Except his family recognized a side of le Carré that, while not some secret double life, didn’t neatly fit into the kinds of stories people enjoy telling about a formidable spy master.

“He was fun, genuinely fun,” le Carré’s son, Nicholas Cornwell, a novelist better known by his own pen name Nick Harkaway, told me. “People want him to be serious, but sometimes he was just playful. He was a guy constantly looking for a way to be happy in a world that had been simultaneously very kind and very unkind to him.”

And that letter of wishes? “He is kidding. He knows it’s a ridiculous request and is laughing from beyond the grave with that one.” Though, Harkaway adds, “The implication is still there, right? Like, I’m kidding, but I’m not kidding. Do me proud.”

With the help of his family, Harkaway has set out to do just that. His latest novel, Karla’s Choice, returns to le Carré’s most enduring creations, the intelligence agency nicknamed the Circus and its spy George Smiley. Set in 1963, the story sees a retired Smiley return to Cold War counterintelligence to find a missing Hungarian émigré and potential KGB asset. Things obviously don’t go perfectly to plan, which is fitting because they didn’t go as planned for Harkaway either.

Unlike most sons, he had to run away from home to not join the Circus. How could he return, at this point in his life and career, to carry on his father’s literary legacy without that very legacy overshadowing his own voice?

Not my Circus, not my Smiley

Metaphorically speaking, that is. Speaking with Harkaway, it is evident that he has an enduring love and respect for his father. Their relationship had its complications — what father and son don’t? — but it was also one of laughter, mutual fondness, and a love of sharing the ideas or odd facts they found rummaging about in books, the news, and through life.

However, after studying politics in college and graduating, Harkaway decided he needed to “touch some grass” and get out in the world. He landed a job in the movie industry as a production runner. He made photocopies, went on the coffee runs, got in early and locked up late, that kind of thing.

Harkaway flirted with script writing but soon abandoned the pursuit. He found he could write stories well enough to secure work, but he lacked those ancillary skills that got scripts produced — things like knowing the demographics, recognizing incoming trends, and the elevator pitch.

“I didn’t want to be an underemployed script writer living in an attic in North London,” Harkaway told me. “There is literally no more obnoxious stereotype on Earth.”

He needed a job that would satisfy his creative drive while also making use of his “random grab bag of skills.” With that direction in mind, he decided he would give writing books a try. If that didn’t work out, he decided, he would go retrain to be a lawyer or some such.

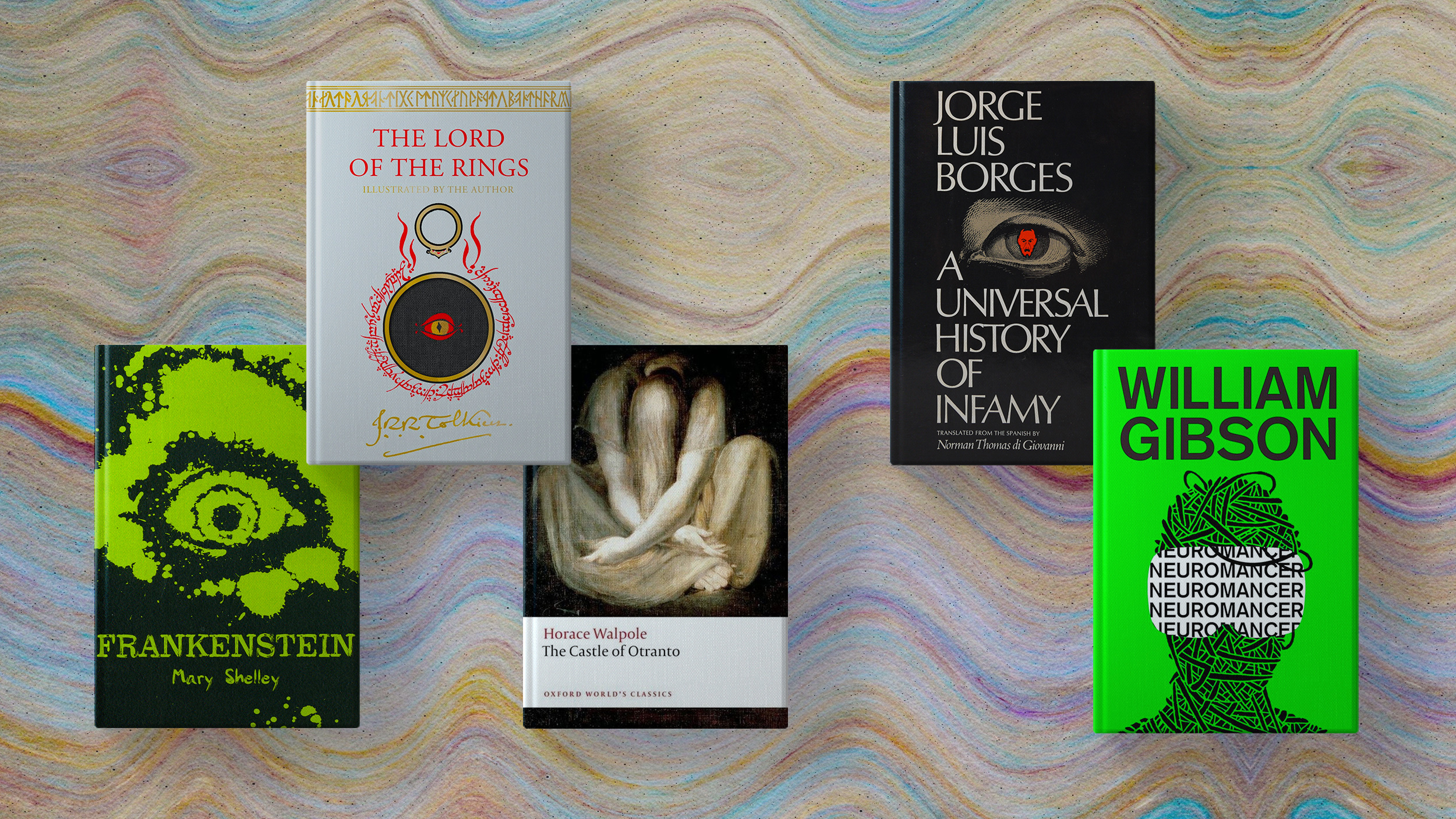

It worked out. His first novel, The Gone-Away World, was published in 2008. The post-apocalyptic tale follows a nameless protagonist on a mission to save a pipeline vital for humanity’s survival. It’s perhaps best summarized as one part Road Warrior, one part Hitchhiker’s Guide, and one part quantum existential horror with a few dashes of 1970s kung-fu flicks (for a bit of kick).

The Gone-Away World received good reviews and was nominated for the Locus and BSFA awards in 2009. And Harkaway kept at it. His other novels include Angelmaker (2013), Tigerman (2014), Gnomon (2017), and Titanium Noir (2023) — each one blending together a literary melange of ideas, genres, scientific concepts, current events, and bits of pop culture.

For the last months, [Smiley] had lived in a daylight world, had espoused its meanings and attitudes, and enjoyed the simple pleasures of other men.

from Karla’s Choice

Harkaway describes his process as “synthesiz[ing] the big picture from disparate pieces,” and it shows when trying to describe the premises of his stories. Even the back-of-the-book blurbs are a joy to read — as though the marketing team was asked to capture a fever dream in a mosaic.

This mosaic typically centers on an idea or trend that Harkaway feels will have important implications for the future. For instance, in the world of Titanium Noir, there’s a drug that makes people young again but has the side effect of making them 20% larger. It’s also expensive, meaning the rich have become 12-foot-tall giants celebrating their bicentennials with lavish parties. Physical size becomes a metaphor for the social dimorphism and “economic gravities” that influence our own world. Splice in a Blade Runner-style detective story and some Neuromancer vibes, and you’ve got a Harkaway novel.

“I’m a magpie,” Harkaway admits. “I take a little of this and a little of that [until] my nest is the size of a football stadium.”

During this time, Harkaway recalls, le Carré “was very arm’s length” about their shared careers. He was supportive, and two would occasionally discuss an idea in one of Harkaway’s books, but he always claimed to have only dipped into the book, never giving it a proper read. In fact, Harkaway was never certain whether his father had actually read any of his books.

After his father’s death, Harkaway shared this misgiving with his brother Simon. Simon recalled their father making similar claims; however, he also noticed that le Carré was always incredibly well-informed about what things happened to what characters — right down to the specific page numbers.

The son who came into the Cold War

Returning to that letter of wishes, Harkaway told me there are two ways to keep a literary legacy alive in modern publishing. The first is to maintain people’s attention with new projects: new books, new films, and such. The second is to get your books on the national curriculum, so everyone is forced to read them.

“Everybody’s going to hate you for their entire lives,” Harkaway laughs, “but your name will never be forgotten.”

So, Harkaway took some time to compile a list of authors he thought could write promising new novels in his father’s world.

“I had a long list,” Harkway recalls. “It was a good list.”

At the next family meeting, before he could “unfurl the scroll” and enjoy his “hear ye, hear ye” moment, Simon interjected, “I think it should be you.”

Harkaway disagreed for several reasons. He had already spent his professional life “drawing clear waters” between his and his father’s works. Different genres. Different styles. Different tones, vibes, and subject matters. They also had unique life experiences — he made coffee runs; he didn’t interrogate people or tap phone lines. And again, there stood how daunting a request it was.

“This is Dad’s universe, which is weird on a personal level,” Harkaway says. “It’s also one of the iconic narratives of 20th-century literature. Everybody will be waiting for it to go wrong.”

But, he adds, “Suddenly, those reasons why you would never do it become the reasons why you should. If you’re not taking risks creatively, why are you still doing this job? You’re frightened of doing Dad’s universe? Get in there!”

There was a whisper of fear in the older man’s eyes, and Smiley realised he was afraid that once the story was told he’d be left alone again to his life.

from Karla’s Choice

Harkaway set out to write the next book in the Circus series. His initial worry was whether he could find the right voice for the story, or, for that matter, what the right voice even was? His voice or his father’s? If his father’s, would it be his spoken voice or his written voice? If written, the short, stark prose of his earlier works or the more complex musings of his later books?

“I can’t do ventriloquism,” Harkaway confesses. “That’ll drive me insane.”

He needn’t have worried. Turns out, Harkaway had developed a sense for Smiley’s world as a kid listening to his father read his early morning writing to his mother. This breakfast-table osmosis, combined with years of experience as a novelist, helped him find a voice that was simultaneously his own and as much Smiley’s as those given to the character by Alec Guinness, Gary Oldman, and Michael Jayston.

The real challenge came when adapting his self-proclaimed magpie approach. “You can’t meander all over the road [when telling a Smiley story],” Harkaway says. “You have to stay focused.”

He adds, “Mysteries are archeological. You uncover, and you piece together. You need to know what you’re going to find when you start. You need to see the picture, and then you break it, and as you write, you put the pieces back together.”

Rather than consider the changes rising over the horizon, with Karla’s Choice, Harkaway cast his gaze back to the Cold War to examine a sin from the era. That sin was the deep antagonism of the Cold War and how it eroded our sense of compassion and hope. The point was not to accuse with the advantage of hindsight, but to use this moment in history to ask a question: Where do you find humanity in such an entrenched conflict?

“Our side is the one that takes care. That gets people back and knows its own human limit, that some prices are simply too high. Better to lose than become the enemy.”

George Smiley in Karla’s Choice

Smiley offered the perfect protagonist to explore this question. A keen observer of human nature, though with his own blindspots, Smiley is ultimately an idealist who believes the world can be better if someone puts in the work and lives up to the promises of democratic ideals. He’s the kind of character who, Harkaway notes, willingly walks into a broken world to pick up the pieces and try his best to put it back together.

It’s that quality of his father’s character and his world that Harkaway wanted to explore:

“In the seventies, [my father’s novels] felt real. They felt recognizably, humanly real. It was a period of disenchantment of an idea. We were doing things that were as bad as everybody else. Did we have any right to do those things? There was an idealistic, pragmatic conversation happening, very similar to now, and people had to reconcile those things.”

Keep calm and le Carré on

One of Harkaway’s fears did prove prescient: People really did seem ready for him to muck it up. Some reviews opened with confessions of worries that Karla’s Choice would offer only a “crude pastiche” or hollow call to get the brand back together. Perhaps that’s to be expected in our era of forever franchises and endless sequels, but while some did find the outing disappointing, many welcomed the novel, calling it a loving homage, a return to familiar streets, and the perfect introduction to the series.

“I would never have imagined writing Karla’s Choice. I would have told you I wasn’t going to do that, absolutely not,” he says, adding, “I genuinely have no idea what’s going to happen next. I’ve given up making predictions about tomorrow, and there is great freedom in this for me.”

That freedom will keep Harkaway busy for a while. A new play based on his father’s novel The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is set to open on the West End in November, and he has another George Smiley novel in the works. Nor is Harkaway finished with science fiction. His latest book, Sleeper Beach, which takes place in the same universe as Titanium Noir, released earlier this year.

Interestingly, the book that started Harkaway on this new journey of his career has two dedications. The first is, obviously, John le Carré, the novelist. The second is David John Moor Cornwell: father, husband, Germanist, terrible cook, ping-pong player, and much more. And while the former wrote very serious books about very serious topics, the latter made sure they were always fun — a tradition his son continues in their now shared world.

“Spying is magic,” Harkaway says. “Spies can see around corners and disappear into a crowd. They can hear things no one else can hear and see things no one else can see. They can communicate silently. Think of it as magic or technique. It doesn’t matter.”

“The point is that you have to go into the story and think, ‘I’d be good at this. If the circumstances were right, if I was called upon, if it was just me, I could walk into that room, open that safe, and come out with the secret. And no one would ever know I was.’ It all has to feel challengingly, excitingly impossible.”