Why historians can only give Jesus a one-sentence biography

- The historical Jesus is an elusive figure, with scholars agreeing on scant few facts about his life.

- While the Gospels contain biographical information, they blend it with legends and shared cultural narratives handed down from earlier Christians.

- For the last 2,000 years, Jesus’ story has been continually retold to express hope, identity, and moral values in an unforgiving world.

Who was Jesus of Nazareth? As one of the most important figures in world history, you’ll likely have a ready answer to this question. Many will picture a man with long, flowing hair and improbably blue eyes garbed in white robes. He could be walking on water, helping the blind to see, teaching a favorite parable, or suffering on the cross. Maybe the scene in your mind is illuminated in stained glass or gilded in medieval splendor or kindled in the Earthly light of a Dutch masterpiece.

I’ll wager you didn’t answer my question with one of your own: “Which Jesus do you mean?” Yet, in some ways, it’s an appropriate response. That’s because the historical Jesus has remained an elusive figure for the past 2,000 years, and in his absence, believers and nonbelievers alike have colored him in strikingly different lights.

Consider: Jesus’ teachings inspired the Quakers and Amish to pursue lives of contemplative simplicity, yet prosperity megachurches offer hallelujahs to the same Jesus when preaching their health-and-wealth sermons. Jesus’ words have liberated the spirits of oppressed people around the world, even while their fellow Christians have colonized or otherwise oppressed them. Then there are history’s many schisms and sectarian quarrels, each one rending ardent believers apart to fight for their interpretation of Jesus’ message.

Can all these interpretations be correct?

To determine who the historical Jesus was, I recently spoke with two scholars of 1st-century Christianity: Elaine Pagels, author and Princeton historian, and Joshua Schachterle, a researcher and writer in the field. I also read several books and articles and listened to online lectures. I discovered that what we know about the historical Jesus barely fills a sentence. The history to find and understand him, however, has filled more than two millennia of scholarship, devotion, and artistic endeavors.

A historical man of mystery

So, let’s try again: Who was Jesus of Nazareth? It turns out that when you ask biblical historians this question, they will likely answer with some version of the following: Jesus was a 1st-century itinerant Jewish preacher who spoke Aramaic and was crucified by the Romans. That’s the scholarly consensus in a nutshell.

Its brevity may surprise some — after all, the New Testament contains 27 books, four of which are dedicated to telling the story of Jesus’ life and ministry. Yet, historians can say surprisingly little about the historical Jesus with a high degree of certainty.

One reason is that record keeping wasn’t as easy or efficient in the ancient world as our modern one. Papyrus was expensive to make, copying books was a by-hand ordeal, and entire libraries could easily be lost to fires or violent flurries of culturicide. Institutions like journalism didn’t exist either, not that many people read anyway.

Literacy rates in the Roman world hovered around 10% — with the literate members of society tending to concentrate in urban areas and among male social elites. Fewer people could write than read, and in the Empire’s rural corners, such as Galilee, literacy would have been more limited (no more than 3% by some estimates).

“[Writing] was a big endeavor,” Schachterle says. “The idea that some guy named Mark walked around with Jesus and jotted down his teachings and then later wrote them all in a book, well, that’s probably not the way it went.”

Even so, the four Gospels of the New Testament — Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John — remain crucial sources of information about the historical Jesus, and historians prize them for the clues they offer about his life. They are also wary of taking the Gospels’ word as, well, gospel.

For one, Schachterle notes, historians have determined that the Gospels were written decades after the events they describe. Historians agree that Mark came first, probably written down around 70 A.D. (or roughly 35 years after Jesus’ death). The last of the canonical four, John, was likely penned between 90–95 A.D. Even if the anonymous writers were eyewitnesses, it is unlikely that their accounts would be entirely accurate, as research shows memories become more embellished and distorted over time.

And they probably weren’t eyewitnesses. Those dates plus other clues — such as the Gospels being written in Greek and showing a reliance on other sources — suggest that the authors weren’t apostles from rural Galilee, but educated, literate elites chronicling the various stories, sayings, and sermons handed down to them by earlier Christians.

One thing that strikes me is that nobody is neutral about Jesus of Nazareth.

Elaine Pagels

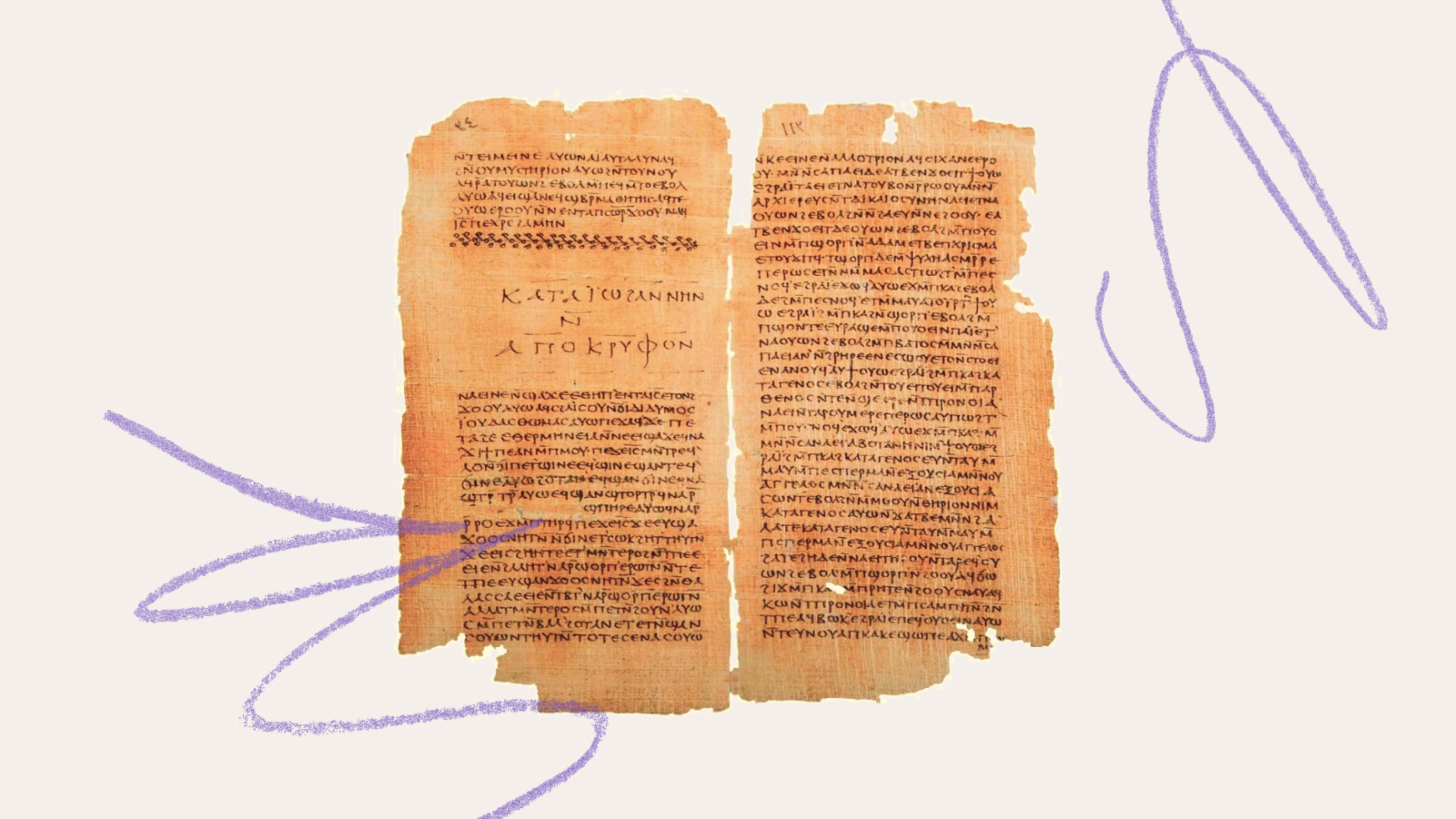

If we consider the surviving manuscripts, this historical gap widens further. The earliest extant copies of the Gospels are fragments from the 2nd century. More complete manuscripts have survived but from as late as the 3rd and 4th centuries. In other words, the earliest manuscripts today’s historians have access to are “copies of copies of copies of copies.”

When compared, those copies have discrepancies. Sometimes, the dispute is between Gospels; sometimes, different copies of the same Gospel disagree. These differences are often insignificant, maybe a typo or word swap. Sometimes they are editorial — for instance, Jesus is quicker to anger in Mark than in Matthew. And sometimes, they contradict each other or the historical record.

Another reason historians don’t read the Gospels as histories: They aren’t. As Pagels told me: “The [Gospels] aren’t history. They have historical content, but they aren’t written to tell you what a history would tell.” Nor were their authors governed by the same rules of sourcing, evidence gathering, and objectivity that modern historians bring to their work — and contemporary readers, in turn, expect from the discipline.

Schachterle agrees: “You cannot just take ancient documents as history because they had a [different] purpose. The Gospels are meant to be theology, but they’re presented narratively, and the theology of the individual gospel shapes the narrative as much as the narrative shapes the message.”

Putting the clues together

Despite the Gospels’ limitations as biographies, biblical historians have devised critical methods to help them peek behind the theological curtain. Broadly speaking, they do this by situating the Gospels within their historical, linguistic, cultural, and sociopolitical contexts. They compare them to each other, other works written at the time, and the evidence gathered through archeology and other ancillary sciences.

These methods don’t allow historians to fully flesh out the story of Jesus’ life. Still, they do allow them to assert greater or lesser probability to the Gospel stories. And the one event scholars are most certain took place in Jesus’ life is, ironically, his death.

Unlike other Gospel stories, Jesus’ crucifixion isn’t only mentioned by Christian writers. Non-Christians of the day also referenced Jesus and attested to his execution for insurrection. These include the Roman historian Tacitus, who mentioned Jesus in The Annals (105 A.D.) and even dated his execution to the time of Pontius Pilate’s governorship over Judea. Note, too, that Tacitus doesn’t allude to Jesus with awe or reverence. He viewed Christianity as a “pernicious superstition” and “disease” that broke out of Judea. From his perspective, the crucifixion would have discredited any claims regarding Jesus’ divinity.

The Romans valued valor, glory, and strength. Crucifixion represented the exact opposite of those attributes — a horrible and humiliating death reserved for the lowest of the low or those seen as a threat to social order. The suffering could last days, and after death, the person’s body would be left on display to serve as a warning. The Romans even forbade burial, leaving the corpses for the crows and other beasts. Claiming your god was crucified and powerless to prevent it wouldn’t have been a convincing argument for Romans like Tacitus.

That 1st-century believers and nonbelievers both reference the crucifixion strongly suggests the Gospels didn’t fabricate this chapter of Jesus’ life. Their authors had to acknowledge the harsh reality of an undeniable fact and come to grips with why it happened — an understanding we can see take shape and evolve through the Gospels’ unique versions of the story.

“One thing that strikes me is that nobody is neutral about Jesus of Nazareth,” Pagels told me. “They either love him or they hate him. He must have been a very compelling figure.”

Important questions remain about how exactly the crucifixion played out. For example, the Synoptic Gospels date Jesus’ death to the day of Passover, while John dates it to the day before Passover. The Gospels also present differing accounts of Jesus’ questioning before Pontius Pilate. Yet, as a matter of historical record, Jesus’ fate seems clear.

Similar methods can be used to suggest which Gospel stories likely didn’t happen. To pick just one: The Gospel of Luke claims Joseph and Mary traveled to Joseph’s ancestral hometown of Bethlehem for a census ordered by Caesar Augustus. However, there are several problems with this account.

First, it’s dubious that any census would require someone to register at their ancestral hometown when taxation was based on people’s present homes and assets (to say nothing of the whole project of figuring out who your ancestors are or which one should count toward the census tally). Luke also mentions that the census was conducted by Quirinius, a governor of Syria. However, this contradicts Matthew’s birth narrative, which takes place when Judea was ruled by Herod the Great, who died ten years before Quirinius’ rule.

The event is likely a narrative device used to have Jesus of Nazareth born in Bethlehem — perhaps to fulfill the author’s understanding of biblical prophecy. Further contradictions between Luke and Matthew make it a challenge for historians to say much of Jesus’ birth other than he was born.

“Seeking a single birth narrative, we find instead tapestries woven from disparate threads,” Pagels writes in Miracles and Wonder. “As for what actually happened — divine miracle, human dilemma, or both — who can say?”

Of course, I’ve simplified these examples. For these or any other Gospel story, historians have more evidence, arguments, points of comparison, and critical methods than I can outline in a single article. Nor is this evidence static. New discoveries in archeology, philology, and other fields may one day illuminate whole new chapters of Jesus’ story.

My goal isn’t to settle any argument. It’s simply to demonstrate how historians critically approach the Bible and why such a close reading of the Gospels presents more questions than answers when it comes to knowing the historical Jesus.

“People are still reinterpreting [the Bible], still understanding it in different ways and coming up with new insights. I think that is absolutely fascinating. You would think that we’d be long done with it, but there’s always new ways to look at it and new discoveries to be made,” Schachterle says.

Spreading the good news

The Gospels are full of stories about Jesus, but none should be read as a biographical account. That’s not to say they don’t hold immense value for Christians and nonbelievers. Pagels, Schachterle, and scores of other scholars wouldn’t have spent their lives studying these and the other books of the Bible if they thought otherwise.

The question then is, how should modern readers approach the Gospels? After my reading and conversations, the best answer I have is simply on their own merits.

People are still reinterpreting [the Bible], still understanding it in different ways and coming up with new insights.

Joshua Schachterle

While the Gospels incorporate history, they also mix in myths, legends, parables, theophany, philosophy, and cultural narratives shared throughout the Mediterranean world. (For instance, here are striking similarities between the miracles performed by Jesus and those of Apollonius of Tyana.) This process of borrowing, blending, and inventing led the Gospel writers to, according to Pagels, craft their own genre. They called the genre evangelion, which in ancient Greek means “good news.” The word gives us our modern evangelism, and when translated into Old English, evangelion becomes godspel or, in modern English, gospel.

Each Gospel tells different stories about Jesus or emphasizes their shared stories differently. In doing so, they share unique theologies through Jesus. In Mark, Jesus is a chosen but misunderstood messenger. In Matthew, he is a Messianic savior, and in Luke, the savior of all. Meanwhile, John downplays Jesus’ humanity in favor of his godhood (“Word was God” and the “Word became flesh and lived among us”).

“If you read [the Gospels] as one story and smash them all together, you can rationalize things because people are really good at that kind of thing,” Schachterle said. “But if you read them individually, as their own thing, you’ll see that they are trying to tell four different stories.”

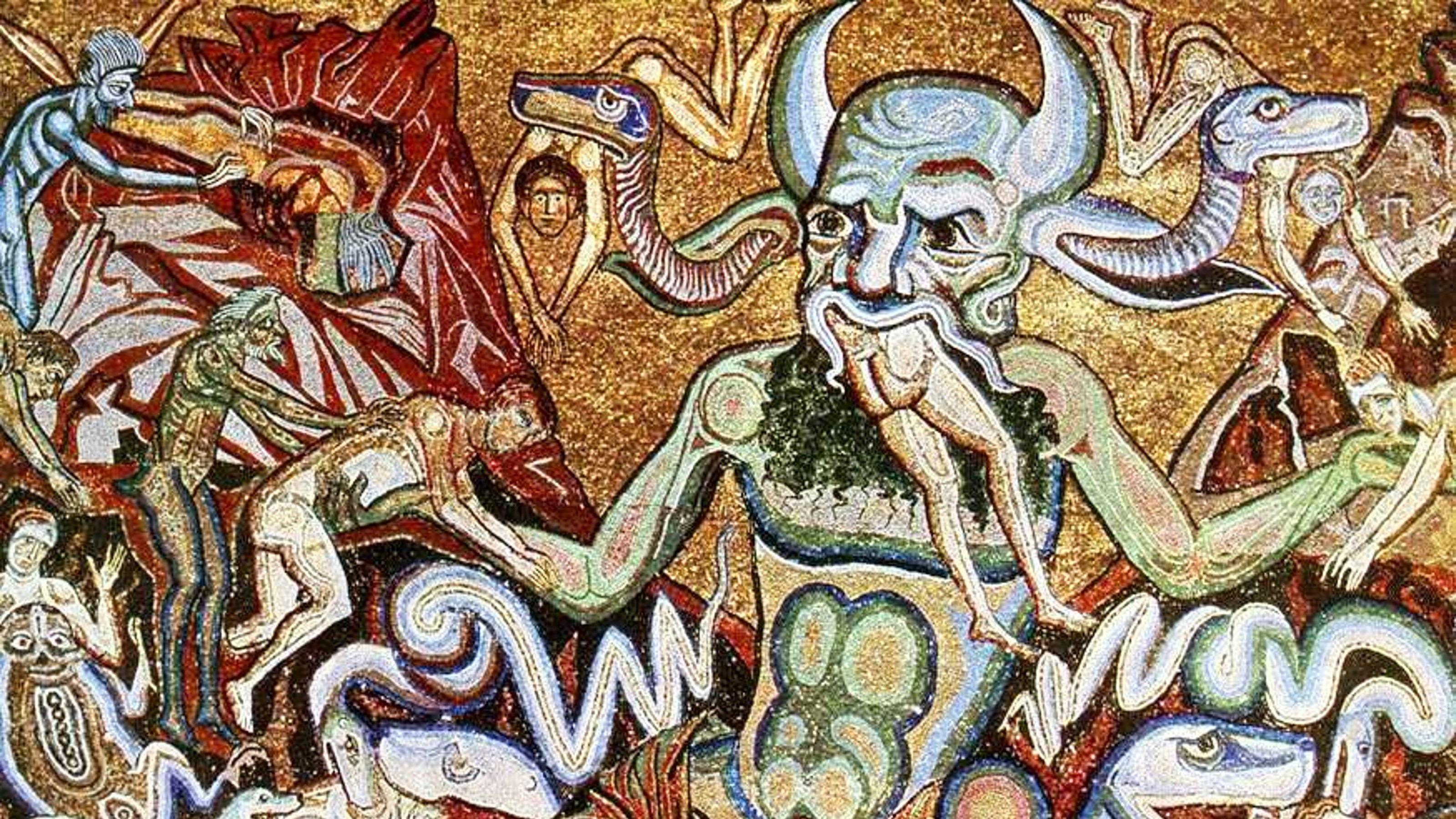

If there is a through line, it is not the historical Jesus, but in how the Gospel authors explore the human condition through his story — a condition of suffering and injustice but with an indelible hope of something better found in shared fellowship. To see what I mean, simply consider the most striking story shared in all four Gospels: Jesus’ resurrection.

In the ancient world, gods, heroes, and even Caesars were resurrected with fair regularity (the latter requiring Senate approval, naturally). But as Pagels points out, Jesus’ story “democratized resurrection.” He taught that every person had an intrinsic value and moral worth, and this value made them worthy of honor and love — if not now in the Roman Empire than in the Kingdom of God to come.

“The stories of the Bible start in the world that we live in — a world in which people are dominated, suffering, oppressed. There’s injustice, disease, death. But the stories typically move into hope,” Pagels says. “It’s that move into hope, when hope seems completely empty and impossible. That is what is so moving about these stories.”

It’s a powerful message and, as Pagels pointed out, one that has resonated with artists, storytellers, and thinkers ever since. Like the Gospels, these works, from Marc Chagall’s vivid crucifixions to films such as Son of Man (2006), aren’t concerned with historical accuracy. They instead infuse these shared narratives with new symbols and allegory to reimagine and revitalize the good news for a new generation.

One last time then: Who was Jesus of Nazareth? When it comes to the historical Jesus, I don’t know much more than when I started; I may even know less, though with more clarity.

Suppose we’re asking about the Jesus of the Gospels. In that case, I’ll borrow a metaphor from Pagels and answer that he is a prism, a figure that refracts “the light of the gospel stories with overlapping perspectives” to tint the human condition — sometimes in darker shades but more often in lighter hues.

“For 2000 years because people keep picking up on different aspects of the story or sometimes the same aspects in different contexts. They put their lives into the story. The story becomes a template for something that they want to say,” Pagels says. Because of this, she adds, “It’s still good news even now for people all over the world.”